Resettlement work

Key findings

- Resettlement requires multiple agencies to work together to address the needs of the child. Strong partnership working relies on shared goals and objectives, and benefits from strong and dedicated leadership.

- A high staff turnover can be a barrier to partnership working. Evaluations have found that there is a benefit to creating capacity to deliver new activities in house by training existing staff in key areas.

- Resettlement works best when it is a desistance-focused, holistic response tailored to the specific needs of the individual child. Engaging the child in their own resettlement is vital, and the work should be flexible rather than trying to fit the child into existing processes. ‘Constructive Resettlement’ is an approach to facilitating the transition from custody to community which places an emphasis on the development of children’s pro-social identity.

- The work to resettle the child should begin immediately when they are received into custody. Planning should take a long-term approach and aim for continuity between custody and community. The transition from custody to community can be traumatic, and Release on Temporary Licence (RoTL), when deployed purposefully, can help to prepare children for release.

- Many children in custody have educational deficits and early training to address these deficits is vital. Accommodation is another high priority area for successful resettlement, and children released from custody need to have their accommodation settled before they are released.

- Girls make up a very small part of the custodial caseload and face unique concerns. Resettlement work needs to prioritise any safeguarding and welfare needs, and work may also be required to help girls forge positive, healthy relationships

Background

Youth resettlement refers to resettling those released from the youth custodial estate while still under the age of 18, and hence still legally children. It is a multi-agency endeavour between the custodial establishment, the youth justice service (YJS), and providers of services such as health, addiction services, education and accommodation.

With only a dozen children serving more than four years in custody at any one time, most children sentenced to custody will be returned to the community while still young. The general decrease in the size of the custodial cohort and the relative increase in the complexity and seriousness of those that remain has introduced some new challenges for the resettlement of children. Key statistics as follows:

- the change in the size of the youth custodial estate has been downwards and significant; the average population falling from 2,046 in October 2011 to 515 in October 2021 (with just 18 girls)

- for the July to September 2020 cohort, the 12-month reoffending rate for children released from custody was 65 per cent

- the length of time spent in custody has risen as the numbers have dropped, reflecting that those remaining have committed more serious offences. The percentage of custodial episodes lasting more than six months increased from 20 per cent of cases in 2015 to 30 per cent of cases in 2020

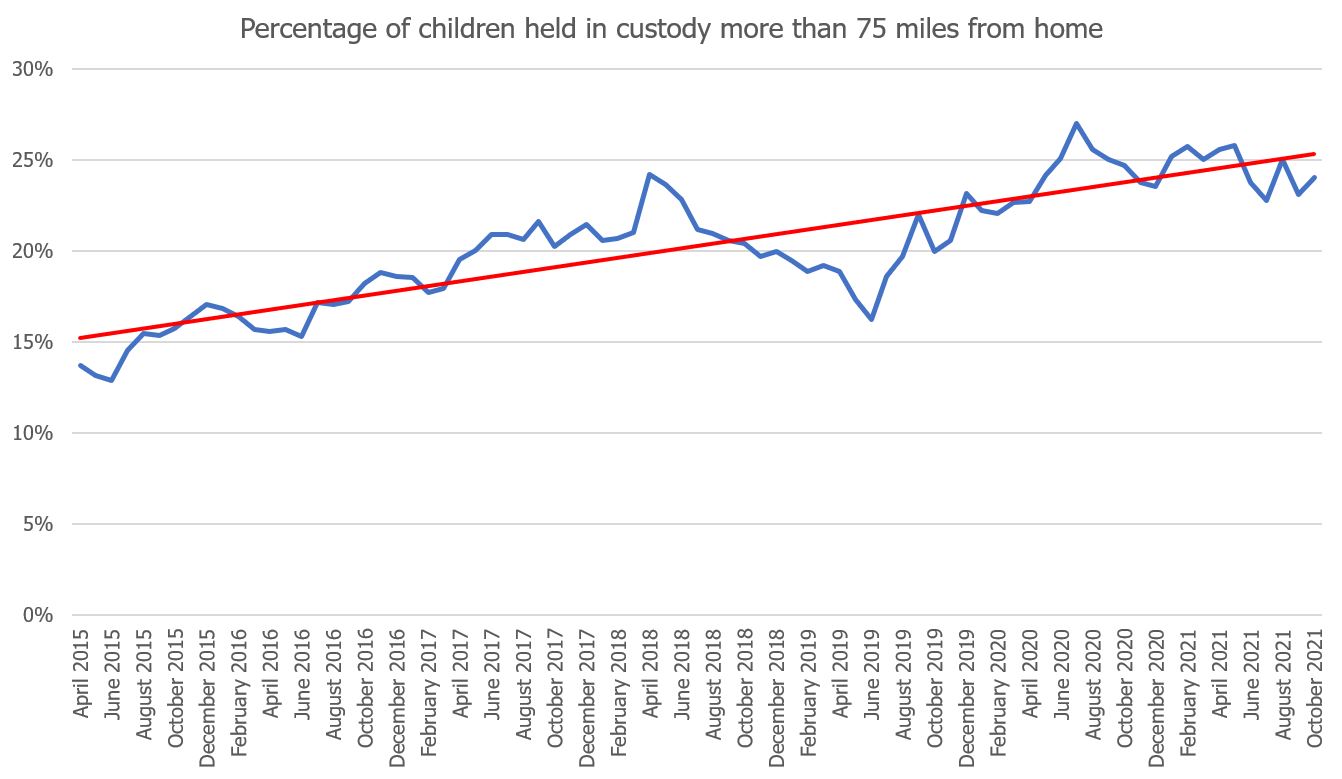

- with the decrease in size of the youth custody cohort, a number of youth custodial institutions have been closed and so children are more likely to be detained further from home, making it harder to maintain links to the area to which they will be released. In October 2021, 24 per cent of children in custody were being held in institutions 75 miles or more from their home, up from 16 per cent in October 2015.

Summary of the evidence

Based upon a review of the literature, the following five-phase resettlement pyramid has been developed to outline the building blocks necessary for positive outcomes for children. The pyramid has links to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, Integrated Cognitive Antisocial Potential (ICAP) theory, and desistance theory.

Partnership working

Resettlement requires multiple agencies to work together to address the needs of the child. Strong partnership working relies on shared goals and objectives, and benefits from strong and dedicated leadership. The most important partnership is between the YJS and the custodial establishment, and good communication between these two partners is critical to successful resettlement.

A holistic and integrated approach can allow providers to accurately model available services, and so avoid duplication of effort and provide a stronger local offer. Specialised groups within the multi-agency provision can tackle particular issues, such as health issues or gang involvement, enabling greater progress to be made, and allowing for more in-depth discussions between key agencies. Strong inter-agency working can lead to other benefits such as improved information sharing protocols and enhanced relationships between agencies. There are benefits from having a dedicated project manager who holds others to a schedule, supports information sharing, co-ordinates partners, and generally maintains momentum.

![]() Find out more about partnerships and services

Find out more about partnerships and services

Staff training and retention

Evaluations have found that there is a benefit to creating capacity to deliver new activities in house by training existing staff in key areas such as trauma, SEND, and case management skills. Keeping this expertise in house ensures that skills remain even when some staff move onto different roles.

During the resettlement consortia pilots, a high turnover of staff in some YJSs was found to be a barrier to resettlement, with additional staff having to be trained in the enhanced offer available. A high staff turnover can also be a barrier to partnership working, with relationships between staff in different agencies needing to be re-established.

Personalisation and engagement

A six-year NACRO-led Beyond Youth Custody (BYC) project concluded that resettlement was most successful when a personal journey for the young person with a clear shift from a pro-offending identity to one that encouraged a positive and constructive future. It was concluded that effective resettlement required all services to focus upon facilitating this shift in identity. The project led to the identification of five general resettlement principles (known as the five Cs):

- Constructive: centred on identity shift; future oriented; motivating; strengths based; empowering

- Co-created: inclusive of the child and their supporters

- Customised: individual and diverse wraparound support

- Consistent: resettlement focus from the start; seamless; enhanced at transitions; stable relationships

- Co-ordinated: managed widespread partnership across sectors

The video below further summarises the five C’s.

Disclaimer: an external platform has been used to host this video. Recommendations for further viewing may appear at the end of the video and are beyond our control.

Engaging children in their own resettlement is vital to success. They should be motivated to comply because they recognise the benefits to themselves, and because they trust the staff helping them. Involvement in planning and co-creation of plans is crucial so that children can understand how interventions and services will help them to reach the new self-identity and the goals they have identified. Flexibility is also important to children and an approach that works with the interests and personality of the child (rather than attempting to fit the child into a standardised service) can generate stronger engagement and commitment. Since many children leaving custody have had very chaotic lives, providing a stable, consistent and reliable service is important. Procedural justice is important too for children so that they feel that the work of those they are engaging with is legitimate and to avoid feelings of resentment.

Resettlement planning must also consider the diversity needs of children and how structural vulnerabilities and social injustices linked to their diversity characteristics can act as a barrier to successful resettlement. Marginalised groups may need additional work on empowerment and may benefit from partnership working with community representatives to develop a sense of community and put in place strategies to tackle discrimination.

Preparation for release

All activities within custody should have a view to the release and resettlement of the child. Planning should, from the point of entry or even earlier, be conducted with a focus on resettlement and on what needs to change to reduce the likelihood of further offending post-release. Planning should thus take a long-term approach, rather than simply laying out what programmes the child will undertake in custody and how their behaviour should be managed. Custodial establishments should seek to facilitate maximum access for community agencies to children in custody, providing both time and facilities for resettlement work. Continuous service delivery between custody and community is important, providing the best chances for successful resettlement; work and programmes commenced in custody should continue in the community.

Transition from custody to community can be traumatic. Children can be disorientated by the move away from a very structured routine and they need to re-establish relationships with those in the community. Reoffending and breach are most common in the critical period just after release, and it is thus important that the child has a clear schedule of community supervision at the point of release; having a clear plan in place provides some structure to the child. It is also important to increase the amount of contact with family and other significant adults in the weeks leading up to release.

Release on Temporary Licence (RoTL) can be integral to preparation for release when deployed purposefully, e.g. allowing the child to view accommodation prior to release, attend training, education or employment taster days or job fairs, and to see family and maintain connections in the community.

The declining custodial numbers mean that children are held in fewer custodial establishments and these are now often further from the child’s home area. This can be a barrier to resettlement, making it harder for community staff to attend meetings or visit and discuss resettlement with the child, and making it harder for custody-based staff to deal with community providers, since typically they will be dealing with a larger number of different communities. It is also more difficult for families to visit regularly.

Education and accommodation

Establishing a return to education should begin in custody as soon as possible. Many children in custody have had poor attendance and engagement with schools and will struggle to return to education unless they receive some training to address educational deficits. Likewise, for children interested in specific vocational courses and qualifications, establishments need to find a way to facilitate these pathways, e.g. assisting children to take the health and safety card tests while in custody if interested in a career in construction.

Accommodation is a very high priority area for successful resettlement and also one of the areas that can be most problematic, as found within the evaluation of the resettlement consortia. Children released from custody need to have their accommodation settled before they are released to prevent homelessness, associations with offending peers, and difficulties in terms of applying for other local services.

Resettlement of girls

Each girl needs an individualised approach to resettlement and this approach must consider the way gender affects the needs of the child. Notably, many of the pathways and offending-related factors are different for girls compared to those for boys, with girls more likely to have pathways into crime based on their vulnerabilities. Girls in custody are three times as likely to have been the victim of sexual violence compared to boys, twice as likely to have been in care before they were incarcerated, and one and a half times more likely to report violence at home. Some girls will have family responsibilities, either children of their own or caring responsibilities for older relatives, and these can be greatly disrupted by custody.

Resettlement work needs to prioritise these safeguarding and welfare needs, and girls must have confidence that these needs are being addressed through their own early involvement in resettlement planning. Family dynamics and peer associations that can encourage offending need to be addressed through interventions and programmes that help girls to forge positive, healthy relationships and identify and understand how they are influenced by interactions with others.

Girls make up only five percent of the youth custodial estate and so there are few institutions catering to them. This means that girls are often placed further from home than boys, where distance from home is already an issue.

Inspection data

In our 2022 Annual Report (PDF, 1 MB), we reviewed the findings over a 12 month period (33 inspections between October 2021 and October 2022) and concluded that the majority of inspected services were now delivering effective resettlement interventions. Almost all of the youth justice services (YJSs) inspected had in place, or were developing, a standalone resettlement policy that promoted a high-quality, constructive and personalised resettlement service for all children. Where policies were effective, they addressed all aspects of ‘constructive resettlement’, and there were effective and collaborative governance arrangements for overseeing the resettlement activity. This was not an area of intervention left simply for the YJS to coordinate, and there was a commitment from partners to support effective joint agency working. As a consequence, information-sharing and communication between services and individuals had developed significantly since our previous thematic inspection.

One point of caution was that some YJSs needed to plan for provision earlier in the sentence than they were currently doing, possibly reflecting a need for ETE partners to engage with the resettlement activity earlier in the sentence.

Between January and October 2022, we rated seven YJSs as ‘Outstanding’ in resettlement. An effective practice guide was produced to draw out the learning from these services.

![]() Find out more about resettlement effective practice (PDF, 2 MB)

Find out more about resettlement effective practice (PDF, 2 MB)

Bateman, T., Hazel, N. and Wright, S. (2013). Resettlement of young people leaving custody: Lessons from the literature. London: Beyond Youth Custody.

Beyond Youth Custody (2015). Effective Resettlement of children: Lessons from Beyond Youth Custody.

Beyond Youth Custody (2014). Engaging children in resettlement: A Practitioners Guide.

Beyond Youth Custody (2014). Resettlement of girls and young women: A practitioner’s guide.

Day, A-M. (2021). Constructive Resettlement Pathfinder Evaluation: Perspectives from practice. Interim report. Keele University.

Hazel, N., Goodfellow, P., Liddle, M., Bateman, T. and Pitts, J. (2017). “Now all I care about is my future”: Supporting the shift – Framework for effective resettlement of young people leaving custody. London: Beyond Youth Custody.

Hazel, N. (2022). Resettlement of children after custody. Clinks.

Paterson-Young, C., Hazenberg, R. and Bajwa-Patel, M. (2019). The Social Impact of Secure accommodation on Young People in the Criminal Justice System. London: Palgrave.

Youth Justice Board (2012). Resettlement in England and Wales: Key Policy and Practice Messages from Research. London: Youth Justice Board.

Youth Justice Board (2018a). How to make resettlement constructive. London: Youth Justice Board.

Youth Justice Board (2018b). Youth Justice Resettlement Consortia: A process evaluation – Final Report. London: Youth Justice Board.

Back to Specific types of delivery Next: Youth to adult transitions

Last updated: 27 October 2023