Implementation and delivery

Key findings

- The delivery of services should be consistent, integrated and sequenced, with interventions combining holistically to address individual risks and needs and build upon strengths.

- The literature emphasises the importance of maintaining responsivity, so that delivery remains tailored to the individual and positive, trusting relationships continue to build.

- Attention should be given to promoting compliance. Instances of non-compliance and relapse should be dealt with in a proportionate, fair and transparent manner – procedural justice indicates that the perceived fairness of processes affects how people respond.

Background

There must be a strong and natural connection between planning and implementation, maintaining a personalised approach which fully engages the service user. Where plans are broken down into a number of ‘steps’, delivery should be tailored accordingly.

Summary of the evidence

Consistent, integrated and sequenced delivery

Research studies indicate that desistance from crime is more likely where the delivery of services is consistent and integrated, with sufficient continuity and consolidation of learning. Interventions should combine holistically to address individual risks and needs and build upon strengths. Sufficient emphasis should be placed on helping the service user overcome practical obstacles to desistance.

Sequencing and alignment are also important to ensure that the most immediate needs are addressed first; only after some stability has been established can work be effectively undertaken on additional needs.

Maintaining positive relationships

The literature emphasises the importance of maintaining responsivity, so that delivery remains tailored to the individual and positive, trusting relationships continue to build. Practitioners need to maintain a balance between encouragement and ‘pushing’, with due regard for service user autonomy. Wherever possible, practitioners should act as positive and motivating role models for those being supervised, use natural opportunities to demonstrate thinking and behavioural skills, and work with service users to seek out solutions through problem-solving advice.

Promoting compliance and addressing non-compliance

Attention should be given to promoting compliance, including: (i) helping the service user to recognise the positive changes and benefits from desistance; and (ii) taking full account of personal circumstances that might make compliance more difficult and working with the service user to overcome such difficulties.

As part of the exercising of legitimate authority, the consequences of non-compliance should be explained to the service user. Instances of non-compliance and relapse should be dealt with in a proportionate, fair and transparent manner – procedural justice indicates that the perceived fairness of processes affects how people view those in authority and subsequently respond.

After enforcement action, re-engaging constructively with the service users is vital to avoid a negative cycle of repeated failure to comply.

![]() Find out more about procedural justice

Find out more about procedural justice

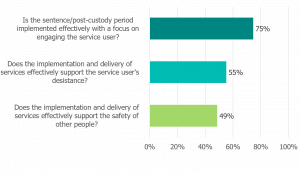

The findings below are from our full round of probation inspections conducted between June 2018 and June 2019. We examined over 3,000 cases, with our inspectors considering whether the delivery of services was effectively engaging the servicer user, supporting their desistance, and keeping other people safe.

We saw many examples of good practice involving the following:

We saw many examples of good practice involving the following:

- relevant referrals being made in a timely manner

- consideration being given to the sequencing of interventions, with interventions provided in the most effective order

- relationships with relevant agencies being well established, supporting the integration of services and more seamless pathways of delivery.

However, too often we found that interventions were not being delivered within the key areas identified in assessment and planning stages. Reasons included referrals not being made, service users being unwilling to undertake the intervention, the intervention not being available in the area, or the service user remaining on a waiting list. Not having clear communication with other agencies was a clear barrier.

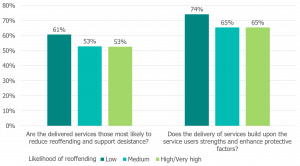

We found differences according to the service user’s likelihood of reoffending, with services more likely to be judged sufficient – both in terms of supporting desistance and building upon strengths – for those with a low likelihood of reoffending.

Stephenson, Z., Harkins, L. and Woodhams, J. (2013). ‘The sequencing of interventions with offenders: An addition to the responsivity principle’, Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice, 13, pp. 429-455.