Procedural justice

Key findings

- There are four key principles of procedural justice: voice, neutrality, respect and trust. Adherence to these principles is linked to improved compliance and positive outcomes.

- Service users have stressed the importance of their relationships with individual practitioners, stating that they value officers who are respectful, non-judgemental, consistent, fair and accountable.

- Service users tend to report that they value being listened to, making sure that they have a chance to ‘tell their story’.

- Research has found that the way in which supervision is experienced by service users will likely have an impact on the outcome of their probation.

Background

According to procedural justice theory, if people feel they are treated in a procedurally fair and just way, starting from the very first contact, they will view those in authority as more legitimate and respect them more. They are more likely to comply and engage, even when the outcomes of the decisions or processes are unfavourable or inconvenient.

The video below, produced by HM Prison and Probation Service, elaborates upon the four key principles of procedural justice.

Disclaimer: an external platform has been used to host this video. Recommendations for further viewing may appear at the end of the video and are beyond our control.

Summary of the evidence

Why is procedural justice important?

Research from different settings, including probation, shows how procedural justice influences people’s respect for, and compliance with, rules and authority. Service users have stated that they value officers who are respectful, non-judgemental, consistent, fair and accountable.

Better perceptions of procedural justice and positive service user experiences have been linked to:

- significantly greater compliance

- fewer rule violations

- less reoffending while under supervision in the community.

Conversely, where service users report not getting on well with their probation officer, resulting behaviours can include not turning up to appointments, or refusing to engage in any meaningful way.

How can procedural justice be put into practice?

Research from across settings shows how procedural justice can be put into practice. Specific examples are as follows:

- offering people the chance to ask questions and responding appropriately to these questions

- explaining how processes work and why

- explaining how decisions are made before a procedure starts and what is considered

- making sure people have a chance to ‘tell their story’

- explaining reasons behind decisions

- making a conscious effort to be approachable

- encouraging people in their efforts to change and succeed

- asking how procedures and treatment could be developed.

Alignment to other research findings

There are obvious areas of overlap between procedural justice and the research relating to desistance and supervision skills. For example, the need to develop positive practitioner/service user relationships which are supportive but challenging when necessary, with appropriate disclosure. The importance of user voice is another constant theme. Service users report that they value being listened to, and for their probation officer to take the time to recognise them as an individual, demonstrate empathy and show a genuine concern for their wellbeing. Service users then feel more able to open up and talk.

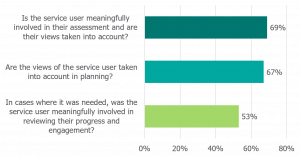

In our full round of probation inspections completed during 2018/2019, we examined over 3,000 cases with our inspectors considering whether the service user was meaningfully involved at key stages. The figure below illustrates that meaningful involvement fell from just over two-thirds of cases at the assessment stage to just over a half of the cases at the reviewing stage.

Blasko, B.L. and Taxman, F.S. (2018). ‘Are Supervision Practices Procedurally Fair? Development and Predictive Utility of a Procedural Justice Measure for Use in Community Corrections Settings’, Criminal Justice & Behavior, 45(3), pp. 402-420.

Manchak, S.M., Kennealy, P.J. and Skeem, J.L. (2014). ‘Officer-Offender Relationship Quality Matters: Supervision Process as Evidence-Based Practice’, The Journal of American Probation and Parole Association Perspectives, 38, pp. 57-70.

Tyler, T.R. (2008). ‘Procedural justice and the courts’, Court Review, 44(1/2), pp. 26-31.