Case supervision overview

Content

Case supervision in context

What does effective supervision look like?

Risk, Need, Responsivity

Applying the risk, need and responsivity principles

Back to home page Next section: Engagement in case supervision

Case supervision in context

Case supervision is the core responsibility of the probation practitioner, who oversees and is responsible for the effective delivery of the sentence of the court. The practitioner needs to build an influential relationship that can balance care with control to support desistance and prevent further victims of crime.

Paul Senior (2016) explained that it is important to recognise that ‘The world of probation operates in and around four major systems of social organisation – the correctional system, the social welfare system, the treatment system and the community’.1 The probation practitioner must navigate all four systems as they work to support an individual through their period of supervision. In probation work there has always been a degree of tension between caring for individuals who have broken the law and controlling and reducing their criminal behaviour. The imbalance of power can be perceived as oppressive and demotivating for the individual under supervision. A skilful practitioner whose response is authentic and who is able to express clear values honestly can enable the service user to view the supervision as legitimate and increase their motivation and participation in the process of change. This is sometimes referred to as procedural justice.

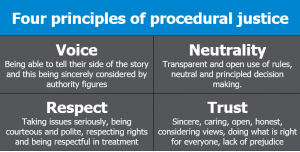

The principles of procedural justice focus on voice, neutrality, respect and trust, as outlined below. Further information is available in the Academic Insights paper ‘Supervision Skills for Probation Practitioners’ (Peter Raynor (2019), HM Inspectorate of Probation).

Additional information can be found on the GOV.UK website, ‘Procedural Justice’ (Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation service. (2019). Gov.uk).

Research indicates that people are most likely to be engaged with and accepting of the outcomes of a process if they believe it to be both fair and legitimate. In addition, a plan is more likely to address service users’ needs where they are engaged as ‘active collaborators’ (Stephenson et al., 2017).2

Probation work is distinctive in that those who are under supervision are attending because they have to. It can be a challenge to achieve sincere engagement in the context of an involuntary relationship. Understanding and working with the individual’s description of their problems is at the heart of facilitating meaningful change and a key feature of supporting desistance.3 A skilful probation practitioner develops an influential relationship with the individual. This, combined with practical help and better access to support services, enables the individual to achieve better control of their actions.

Managing and displaying emotions is critical to effective practice. Practitioners use emotions to create better relationships with service users, encourage compliance, support desistance, and assess and manage risk more effectively. Jake Phillips et al explore this further in our Academic Insights paper.4

The work of the probation practitioner is complex. For each case they need to take account of the individual’s protected characteristics: there is no single solution that can be applied to all. Inspectors assess how well an individual has been engaged and whether the practitioner has taken account of their individual needs, as well as how their profile to reoffend and cause harm to others has been addressed and managed.

Good-quality case supervision provides coordination and oversight of the implementation of the order of the court, and how this is delivered can have a significant impact on outcomes. We know that interventions, such as offending behaviour programmes and support with employment or accommodation, work better when they are correctly targeted and the individual is supported by a probation practitioner with effective supervision skills. Furthermore, the probation practitioner needs to use their professional judgement to assess the individual’s motivation, readiness to change, and potential to cause harm to others. They should use this information to decide how to sequence interventions and address non-compliance.

What does effective supervision look like?

While this guide provides examples of good practice found during inspections, they cannot be applied to all cases. It is imperative that there is an assessment and understanding of the issues, requirements and needs in each case. In particular, practitioners should consider the potential for serious harm and proportionality when planning how to manage a sentence. Andrews and Dowden (2006), among others, argued that medium- and high-risk offenders generally benefit more from intensive correctional interventions and low-risk offenders benefit less from intensive interventions. Being attentive to diversity demands a tailored approach that recognises the different backgrounds and needs of individuals.

Trotter5 noted that prosocial modelling and reinforcement, problem-solving, and cognitive techniques are core skills for reducing recidivism in probation supervision, and that these three skills have generally shown significant associations with recidivism. ‘It seems reasonable to conclude that if probation officers or others who supervise offenders on court orders use evidence-based practice skills, their clients are likely to offend less often’.

Effective probation practice requires attention to both public protection and reducing reoffending. Neither can be achieved in isolation: the skilful practitioner needs to be able to attend to both assessments simultaneously. It is noteworthy that the future NPS operating model defines the probation practitioner’s role as ‘Assess, Protect and Change’.

The pressure of managing high workloads is cited all too frequently as an issue for probation practitioners in our adult inspections. Back in 2007, Ward and Maruna highlighted that increasing workloads and time constraints meant that practitioners prioritised risk rather than rehabilitation.6 Prioritising work to make best use of the time available is an important skill for probation practitioners. They must consider how frequently an individual will be supervised. Shapland et al (2012) identified the importance of regular interaction in the early stages of an order, as evidence suggests reoffending is significantly higher during this period.7

The following good practice examples illustrate how practitioners are able to combine compliance with mandatory criminal justice processes with delivering work that is influential and meaningful to the individual and supports them in avoiding reoffending, while remaining attentive to keeping others safe.

Risk, Need, Responsivity

Case supervision encompasses a multitude of tasks, so the professional probation practitioner needs to be a skilled ‘multi-tasker’. They need to determine the necessary frequency of contact, taking account of the individual’s assessed level of serious risk of harm and risk of reoffending. They must also consider the priorities of monitoring, compliance and enforcement, engagement and the implementation of targeted interventions tailored to meet the individual’s needs. The risk need and responsivity principles have been hard-wired into the probation profession’s understanding of evidence-based practice since the ‘what works’ era and publication of the HMI Probation evidence-based practice guidance in 1998. Drake (2011)8 showed that reoffending rates fell (16 per cent) if the supervision applied the risk, need and responsivity principles.

Applying the risk, need and responsivity principles

Interventions should match the likelihood of reoffending, and offending-related needs should be the focus of targeted interventions. Opportunities to provide integrated services and pathways of delivery, particularly for service users with multiple and complex needs, should be well-developed.

[1] P Senior et al. (2016). Imagining Probation in 2020, British Journal of Community Justice Vol. 14, No.1, pp .9-27

[2] Stephenson, Z., Woodhams, J. and Harkins, L. (2017). ‘The sequencing and delivery of interventions: views of imprisoned for public protection (IPP) prisoners in the UK’, Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice, 17(4), pp. 275-294.

[3] Weaver B. (2016). Offending and Desistance: The importance of social relations.

[4] Phillips J., Westaby C. and Fowler A. (2020/03). Emotional Labour in Probation. HMI Probation.

[5] Trotter, C. (2013). Reducing recidivism through probation supervision: What we know and don’t know from four decades of research. Federal Probation, 77, 43-48

[6] Ward T and Maruna S (2007) Rehabilitation: Beyond the Risk Paradigm. London: Routledge.

[7] Shapland J, Bottoms A, Stephen F, McNeill F, Priede C, Robinson G and Farrall S (2012). The Quality of Probation Supervision – A Literature Review: Summary of Key Messages. Available at: http://cep-probation.org/uploaded_files/quality-of-probation-supervision.

[8] Drake, E. K. (2011). “What Works” in community supervision: Interim report. Olympia: Washington State Institute for Public Policy.