Substance misuse

Key findings

- Within the Offender Assessment System, both drug and alcohol misuse are included as offending-related factors. Drug misuse is scored more highly in relation to predicting general reoffending, while alcohol misuse is scored more highly in relation to predicting violent reoffending.

- Completion rates across a number of relevant treatment requirements have been found to be good – including the Alcohol Treatment Requirement, Drug Rehabilitation Requirement, and Alcohol Abstinence Monitoring Requirement. Appropriate rewards and sanctions can be used to both motivate the service user as well as hold them to account.

- A range of services and interventions have been found to be effective (to differing degrees) for treating substance misuse and reducing reoffending rates, including opioid substitution treatment, psychosocial interventions, brief interventions for alcohol, trauma-informed approaches, and digital/online interventions.

- A number of weaknesses have been identified in relation to continuity of care from custody into the community for those requiring substance misuse treatment.

- ‘Recovery capital’ has been seen to be critical for successful and sustained recovery from substance addiction, with social connection with pro-recovery or non-using peers playing a key role.

Background

Although the link between substance misuse and crime is complex, there is evidence to suggest that a significant number of those committing criminal offences have problematic alcohol or drug use.

Dame Carol Black’s Review of Drugs highlighted the challenges facing service users who require treatment in the community. Cuts in funding, reduced accountability, and the loss of skills, expertise, and capacity in the third sector have all posed challenges for the availability of suitable treatment for those under probation supervision. For those who have spent time in custody, there are significant problems with the transition to community treatment on release.

While two relevant requirements are available which can be attached to community orders or suspended sentence orders – namely the Drug Rehabilitation Requirement (DRR) and the Alcohol Treatment Requirement (ATR) – their use has been consistently low. The Alcohol Abstinence Monitoring requirement is also being rolled out nationally.

Recent policy related to substance misuse has emphasised the need for better treatment for service users in the community, with those recently released from custody identified as especially vulnerable to relapse, reoffending, and drug-related deaths. Reducing dependency is seen to require ‘recovery capital,’ with a focus on housing and meaningful employment.

Summary of the evidence

Identifying substance misuse – Offender Assessment System (OASys)

Within OASys, both drug and alcohol misuse are included as offending-related factors. When considering the association between a range of factors and proven reoffending, a two-year follow-up study reported that general reoffending rates were found to be highest among drug users. Both chronic and binge drinking were strongly associated with violent reoffending, but only moderately with general reoffending.

Treatment requirements

An evaluation which analysed treatment files for 81 service users on an ATR found that 70 percent of the sample successfully completed the treatment, which was fairly high compared to DRRs. This was attributed to the fact that breathalyser testing on the ATR was considered motivational for measuring reductions in alcohol use, whereas, due to the illegal nature of drugs, those who ‘relapse’ with a positive drug test on a DRR may face punitive measures.

With regards to DRRs, in-depth interviews with service users and staff identified factors which both supported and undermined compliance with the order. For service users, barriers included:

- the assessment process

- staffing issues in treatment agencies

- waiting times for interventions

- clashes between probation and treatment appointments

- travel issues and caring responsibilities.

A lack of consequences for continual positive drug tests led some service users to assume staff did not care about their progress.

Probation staff emphasised the following barriers to successful treatment:

- issues with service users’ motivation

- the impact of chronic drug use

- the availability of appropriate services

- the management of breach and compliance.

It has previously been found that interventions are most successful where staff are in a position to reliably detect both service users’ accomplishments and infractions, applying rewards and sanctions where applicable.

Through the Alcohol Abstinence Monitoring Requirement (AAMR), ‘sobriety tags’ can be fitted to service users to monitor alcohol consumption via sweat for up to 120 days. Prosecution or other sanctions are possible for those who do not comply. While pilot evaluations of the scheme revealed high levels of compliance, as well as benefits to general health and wellbeing, service users raised concerns with both the size and comfort of the tag, as well as the stigma associated with wearing it.

The video below, produced by HM Prison and Probation Service, offers a quick guide to alcohol monitoring.

Disclaimer: an external platform has been used to host this video. Recommendations for further viewing may appear at the end of the video and are beyond our control.

Treating substance misuse

Strong links have been found between illicit opioid use and criminal activity, largely acquisitive crimes. Pharmacological interventions, such as opioid substitution treatment (OST), can assist with withdrawal as well as the prevention of relapse – there are no approved medications available for other drugs. OST has been widely evaluated and there is a solid evidence to suggest that this treatment is effective at suppressing heroin use. Crime reduction has also been observed for those remaining in continuous treatment, which often includes access or signposting to a range of additional support services.

Psychosocial interventions, particularly those based on cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT), are often used either as standalone treatment or alongside OST where applicable. These interventions aim to help people create and maintain motivation for behaviour change and recovery, and to gain awareness of and be able to cope with the emotions and urges associated with their substance misuse. While there is some evidence for CBT’s effectiveness when compared to no treatment, this has been found to vary between substances. This approach can be helpful for those with comorbid substance misuse and mental health difficulties.

Building Skills for Recovery is the accredited psychosocial substance misuse programme available both for those in custody and the community. The intervention aims to reduce reoffending behaviour and problematic substance misuse with an eventual goal of recovery. An evaluation of an earlier iteration on the programme found that those who completed it had significantly lower rates of reconviction and longer-time to reconviction than non-completers.

Brief interventions aim to identify actual or potential alcohol problems and motivate an individual to address these, with the intention of filling the gap between primary prevention efforts and more intensive treatments. Although there is little evidence to support the benefits in terms of substance intake, some reduction has been seen in reconviction rates when compared to those service users only provided with an advice leaflet. Some staff who delivered interventions believed they could encourage clients to think more readily and realistically about their drinking behaviours.

Online approaches to treating addiction enable people to access necessary services in a confidential and anonymous manner. As such, digital treatment has the potential to overcome barriers in seeking assistance for substance misuse, including the stigma associated with more visible, traditional services. Breaking Free Online is a digital treatment which focuses on strengthening the user’s recovery and resilience from substance misuse through a range of psychological techniques, with versions for both prison and probation settings. An evaluation of the treatment found significant improvements in user’s alcohol and drug dependence, as well as other aspects of psychosocial functioning.

Trauma-informed approaches

There is increasing recognition that many of those with substance use issue may also have experienced or may still be experiencing trauma, and as such, a trauma-informed approach is recommended. This seeks to avoid re-traumatisation, as well as promoting physical safety and applying strength-based practices. By being focused on the present and emphasising ways of developing resilience and coping, this approach does not require a disclosure of trauma. Only once a service user has established a sense of safety and stabilisation can consideration then be given to directly addressing traumatic memories.

Continuity of care – custody to community

The first few weeks after release from prison are an especially vulnerable time for those using substances. A 2017 evidence review identified a number of weaknesses in the pathway between custody and community:

- almost half of the referrals made by prison treatment services were not received by community treatment service

- limited opportunities to make referrals with unplanned releases from court and no joined-up working with probation services during release planning

- low attendance at appointments or drop-in clinics in the community following release from prison, with limited follow-up on individuals who did not attend.

It was also found that service users were much more likely to engage with treatment in the community where treatment services had made contact with them in custody prior to their release.

Recovery capital

‘Recovery capital’ refers to the resources required to both instigate and sustain recovery from substance abuse, encompassing personal recovery capital, family or social recovery capital, and community recovery capital. Sustained recovery is seen to be best supported through social relationships, which includes moving away from networks where people have addictions towards those which encourage recovery. It is this positive social support which is thought to drive the belief in the individual that change is possible, which is turn instils a sense of hope to provide the energy required to address the challenges associated with recovery from addiction.

![]() Find out more about personal recovery

Find out more about personal recovery

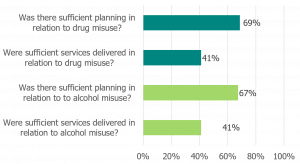

In our core adult inspection programme, there are questions related to addressing drug misuse and alcohol misuse, where they are identified as offending-related factors, at both the planning and intervention stages. Data from our 2018/2019 inspections is set out in the figure below – a drug misuse need had been identified in 47 per cent of the cases, while an alcohol misuse need had been identified in 40 per cent of the cases.

Ashby, J., Horrocks, C. and Kelly, N. (2010). ‘Delivering the Alcohol Treatment Requirements: Assessing the outcomes and impact of coercive treatment for alcohol misuse’, Probation Journal, 58(1), pp. 52-67.

Bailey, K., Trevillion, K. and Gilchrist, G. (2020). ‘We have to put out the fire out first before we start rebuilding the house: practitioners’ experiences of supporting women with histories of substance use, interpersonal abuse, and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder’, Addiction Research & Theory, 28(4), pp. 289-297.

Black, C. (2020). Review of Drugs. London: Home Office.

Elison, S., Davies, G. and Ward, J. (2015). ‘An outcomes evaluation of computerised treatment for problem drinking using Break Free Online’, Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 33(2), pp. 185-196.

Marlowe, D.B. (2003). ‘Integrating substance abuse treatment and criminal justice supervision’. Science and Practice Perspectives, 2(1), pp. 4-14.

Public Health England (2017). An evidence review of the outcomes that can be expected of drug misuse treatment in England. London: Public Health England.

Roberts, E., Turley, C., Piggott, H., Lynch-Huggins, S., Wishart, R. and Kerr, J. (2019). Evaluation of the AAMR tagging pilot: year 2 process evaluation findings. London: NatCen.

Sirdifield, C., Brooker, C. and Marples, R. (2020). ‘Substance misuse and community supervision: a systematic review of the literature, Forensic Science International: Mind and Law, 1, [Online].

Therapeutic Solutions (2011). Review of the Drug Rehabilitation Requirement (DRR). London: Therapeutic Solutions.